One of the underlying concepts of this site is that we were going to try to introduce practical tips to help you implement continuous improvement in a job shop environment while keeping the generic pablum and theories to a minimum. One notable exception is going to be this topic, which is an introduction to the Theory of Constraints.

One really cannot discuss continuous improvement in a job shop environment without at least a brief introduction into the theory of constraints.

It was first introduced in 1984 by Eliyahu Goldratt in his 1984 book titled

The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement.

There have been a number of revisions over the years as the theory has evolved and grown. While this and related articles are a good introduction,

it is still advisable to read the book or listen to the audio book for a more comprehensive study of the theory.

Because of it's importance in job shops, listed below are articles that expand upon the content provided in this article:

The Theory of Constraints can be summarized as "Increasing Your Throughput While Simultaneously Reducing Inventory and Operating Expense By Managing Constraints." In modern manufacturing it is nearly impossible to evenly and efficiently load all your equipment with an equal amount of work. Because of this constraints (bottlenecks) occur in your production processes, where some processes are going to have more work or work at a slower pace than the other processes in the value stream. But it goes deeper than that for job shops, as we often have constraints in material procurement, engineering, information, and worker force training that are just as vital as any piece of equipment or process.

In an assembly line operation, bottlenecks are spotted by producing a value stream map, and can sometimes be overcome by simply redesigning the process to increase production at these points to keep the line moving at the same pace. An example of this would be to split the line and have two of the slower bottleneck machines running the part, then combine the line again after that process.

In job shops, the bottlenecks are neither as simple to identify nor eliminate. Our bottlenecks often only show up when we run certain product mixes, so a value stream map we run one day will not be valid the next. We often have very short runs, so we cannot redesign our processes for every bottleneck. Many of our solutions to bottlenecks need to come from careful planning and scheduling to minimize their impact.

Constraints are anything that inhibit an operation from meeting its goal, which ultimately for businesses is to make money. They can be on the manufacturing floor, in materials, engineering, or anywhere in the system. They are the weakest link in your operation, and they set the pace for your throughput.

Below are some common constraints found in job shops:

Equipment

Equipment can refer to capacity of machine, or flexibility when switching jobs. It can also refer to secondary equipment, like the lifting

capacity of overhead cranes.

Processes

Some processes are often more time consuming than others. For example, a piece of machinery may be built mechanically in a week, but it may

take an additional week to wire and install automation.

People

This includes not enough staff, under-skilled, or lack of cross training. Mental constraints of doing "how things are have always been

done" also can limit output.

Materials

One of the most common constraints is timing raw material delivery with production needs in a made-to-order environment.

Information

The flow of cuttings and engineering drawings to the shop floor is critical. Priorities need to clear and correct. Also, the

information must be usable by the workers.

Scheduling

If the shop floor is not properly scheduled, huge bottlenecks are created

Policy

Includes internal policies such as safety, quality, union contracts, or internal procedures. It can also cover regulatory items, such

as industry standards and government regulations.

Customers

This one is unique to Job Shop environments, as customers change specifications and delivery dates mid-project.

Market

Market refers to producing more than you sell, which will only come into play if you make some stock items.

Keep in mind that these are constraints when everything is running perfectly. While machine breakdowns, absenteeism, or a snow storm are short term constraints, they are not the focus of the Theory of Constraints.

In this article we use the terms "constraint" and "bottleneck" interchangeably for simplicity, but there are differences between the two which we point out in our more comprehensive article on bottlenecks.

The Theory of Constraints provides a simple methodology for managing your constraints:

Identify

Identify your constraints. Sometimes it is as easy as finding where the WIP ends. Other times you may have to rely on time studies or historical data to find them.

Elevate

Do whatever you can do maximize the output at this constraint as it is now. This is where a lot of your lean efforts will be focused in a job shop. It is

also the prime location to roll out standard work in your shop. This will also be the first focus of your scheduling process.

Subordinate

Since the pace of the entire operation depends upon your constraints, all other processes are subordinate to it. Scheduling plays a key role in this in job

shops - you do not want to be running all these are processes all the time or you will be building mountains of WIP and ultimately running insufficiently.

Eliminate

This is often a capital expenditure where you are upgrading equipment. But it could also be working your entire value stream to spread out the

functions of the original bottleneck among several processes, thus eliminating it. However you do it, the goal is to completely eliminate the bottleneck.

Start Over

This is why it is called continuous improvement. Once you've eliminated the bottleneck, start over again and find where the next one is. You have

to be very careful, however, as the inertia created by removing the bottleneck will sometimes slow down the entire system.

But we're not done in job shops, there is an additional step. Since our product mix changes so often, we must do this process for each major variation of products we run. We must also understand that the mix itself creates constraints which would not otherwise exist.

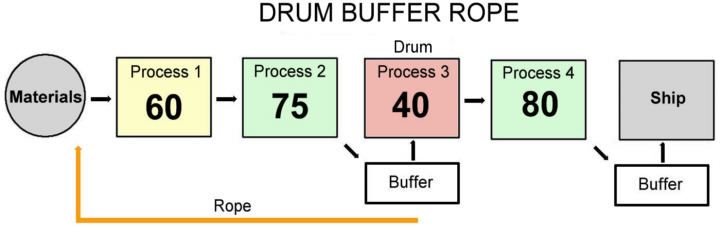

Drum Buffer Rope is a method of scheduling and synchronizing production so that you can keep your constraint operations running at their fastest rate possible

by ensuring that constraints always have the inputs they need and are never waiting. It plays help fulfills steps 2 & 3 from the 5 focusing steps

mentioned above. This is a basic introduction, with a more in-depth analysis provided in our

Drum

The Drum is the constraint. Just like a drumbeat, it is the speed with which operation marches.

Buffer

The buffer is the extra WIP needed in front of the constraint to make sure that it always has enough work and never stops. A second buffer is added before shipping to ensure

problems do not affect the customer.

Rope

The rope is a signal to release more work to refill the buffer of the constraint.

Another of the core tenets of the Theory of Constraints is that standard accounting practices often distort the real financial situation in manufacturing plant. For example, inventory is treated as an asset, regardless if it is sold in standard accounting. Under throughput accounting, only output that has been sold is counted. A stronger emphasis is placed on throughput than cutting expenses, as expenses are finite but throughput theoretically has no limit.

So ultimately, the goal is to "Increase throughput while simultaneously reducing inventory and operating expense."

The four standard measurement associated with throughput accounting are:

Net profit (NP) = throughput - operating expense = T - OE

Return on investment (ROI) = net profit / investment = NP/I

TA Productivity = throughput / operating expense = T/OE

Investment turns (IT) = throughput / investment = T/I

While both are aim at continuous improvement, they have some key differences:

So which is should I use in my job shop? Both. The Theory of Constraints works exceptionally well at identifying the areas to focus on and increasing the velocity with which product flows through your plant. Lean principles work well at optimizing your processes on a lower level by eliminating wastes and optimizing your bottlenecks. You will also find plenty of "low hanging fruit" wastes in your plant, in the office and on the shop floor, that will benefit from lean principles.